inthedrops: a compilation of my work

Before the Giro I spoke to three men – three riders who have all won stages at the race but are more well-known as workers, or gregarios, for others.

Astana veteran Paolo Tiralongo helped Vincenzo Nibali win the Giro in 2013, as well as working for Alberto Contador during his now-nullified 2010 victory. He has also experienced personal triumph at the race, winning stages in 2011 and 2012.

Australian Adam Hansen is riding his fourth Giro in a row for Lotto-Soudal, his sixth overall. A key part of André Greipel’s sprint train, Hansen won a Giro stage back in 2013.

Cannondale-Garmin rider Ramunas Navardauskas was part of the squad that assisted Ryder Hesjedal’s unlikely Giro win in 2012. The Lithuanian wore the pink jersey for two stages that year, and went on to take a stage win of his own a year later.

Here’s what the trio had to say about La Corsa Rosa and their experiences with the race.

Tiralongo: This will be my thirteenth Giro. Cycling has changed a lot since I was young, before there was more room for personal initiative – now everything is focused on the team and the leader.

Hansen: Actually I didn’t follow the Giro, or any professional cycling, before I moved to Europe [In 2003 Hansen swapped mountain biking in Australia for racing at Continental level in Austria.]

Navardauskas: I remember Cipollini. I always heard about big names like that but when you’re a kid you never think that one day you’ll be there too.

Tiralongo: For me, and every Italian rider, it’s the most important race of the season. It’s our home country and we are more visible, more popular than at any other race.

I think that everyone who can finish this race is a hero. Even if you don’t win, the climbs are equally long for all. Cold is cold, rain is rain – it’s the same for everybody.

Hansen: It’s definitely one of my favourite races. I’ve been a few times and every day you’re racing, every day you have a chance. It’ll be my eleventh Grand Tour in a row, and I think the plan is just to keep going.

Navardauskas: It’s been a lucky race for me and I have good memories of it. Sadly I’m not at the race this year but as always work is work – the Giro, Tour, Vuelta, wherever you go it’s always a big responsibility for the team.

Tiralongo: A real gregario is happy when a teammate or leader wins. You’re happy because you know you have contributed to the result. The team has to come first to achieve certain results – it’s the only way.

The victory at Macugnaga [in 2011] was my first. I arrived at the finish with my friend, Alberto Contador, who was my teammate at Astana the year before – we helped each other. The next year I desired the win at Rocca di Cambio [beating Michele Scarponi], and fought for it. They were special moments.

Hansen: For instance when Greipel wins it’s very special because the whole team is working, protecting him from the wind and so on. And you do feel proud of it, and I think that’s one of the good things about being a domestique.

As for my stage win, it was just all the years of riding, all the years of being a domestique – everything paid off in that moment. It felt like the small token or present you get for finally making it. The win was the greatest moment of my cycling career.

The day when I won – it was the kind of day where you want to be in the break because the weather is so bad. In the last ten kilometres I was thinking “the peloton will come or I’ll crash or flat any moment now.” It was an unexpected win.

Navardauskas: When your leader has a chance to win, it’s always bigger. A leader that wins the General Classification has made his career – in the future you can tell your friends, your kids that I was there, I helped that.

Anything is possible – when we started the Giro, Ryder was more of an outsider and then we started getting better as a team, every day more motivated. That win is like a personal win.

Tiralongo: The Giro is the hardest. Its climbs are long and steep, real climbs. Additionally, the weather is more uncertain and it can be really cold. On the other hand the Tour is hotter but the race is more controlled in comparison. The Vuelta is, of course, the hottest and the fastest.

Hansen: The Tour is where results count, where you have more sponsor pressure. At the Vuelta, they bring in young guys and it’s a good chance to build for the Worlds. It gives you more opportunities to have a go too, but it’s also more relaxed – you wake up later and start racing later.

As for the Giro, I think it’s the most traditional Grand Tour. They’re real cycling fans, whereas at the Tour there are more tourists – it’s a big circus. The Giro is more pure in that way.

In terms of racing, I think the Giro is the hardest but the Tour is the hardest to win at. It’s harder to finish the Giro than it is to finish the Tour. The ultimate goal is to complete the set and win a Tour stage too.

Navardauskas: I’ve never done the Vuelta but I think that some years the Giro is much harder than the Tour. The mountains are harder and it has difficult stages. Sometimes there’s really bad weather makes it even harder.

The Tour has a bigger name than the Giro but it’s very hard to do well in either. When you’re in the race you don’t think about comparisons though.

Tiralongo: My two victories are the best. The ugliest memory I have is the 2013 edition. Despite Vincenzo Nibali’s victory it was three weeks of agony for me because I was ill. I didn’t give up though.

Hansen: 2007 was pretty bad – I broke my hand. It was my first Grand Tour and I didn’t know what to expect.

I think the stage last year, going up the Gavia – that was pretty bad. It was a nightmare – we didn’t really know what was going on. There wasn’t really a race going on because you couldn’t see anybody.

Navardauskas: Obviously I had my first stage victory at a Grand Tour there, and I have worn the pink jersey. They are very, very happy memories. From the Grand Tours I have done I can say that every rider has his own very bad day.

I think the worst for me was in 2012, when I rode the Giro a month and a half after I broke my collarbone. On the third stage I crashed – it didn’t break again but for several days after every stage was really hard and exhausting.

Tiralongo: I can’t say one stage but the 2011 edition, won by Contador. I have never seen so many tired riders. There was a lot of climbing despite the alteration of the Zoncolan stage [there was 409km of climbing on the original route].

Hansen: Definitely the Gavia stage. It’s one thing to be cold while you’re racing because you can get heat from that, but it was the descents. When you have fifteen-twenty kilometre descents, you’re just freewheeling and getting colder and colder.

Navardauskas: In 2012, when Hesjedal was our leader and he was in second place. It was the king stage – huge, huge mountains – and I remember it was very hard from the beginning with huge steep climbs. Yeah (laughs) it was just very hard.

Tiralongo: In the Giro I will work for Fabio Aru – I have a lot of experience so that will help. We have a strong team and the aim is to win the Giro. I don’t know if it will be my last participation – it will be up to me to decide when I retire [Tiralongo’s contract runs out this season].

Hansen: It’s very new for the team because we have both Greipel for the sprints and Van Den Broeck as our GC guy. It’s going to be exciting. And, looking at the parcours, maybe there will be chances for me to go on the attack too.

Navardauskas: I was a reserve for the Giro so I had to be ready to race but seeing as I am not going to Italy this is my time to rest after Romandie. Next I will go to Germany [to the Bayern Rundfahrt] and then we will see from there. I just try to get good results and work for the team everywhere I go.

Another five or so hours of precious sleep and I woke up to pouring rain. My phone told me it would be like this all day. Stupid phone.

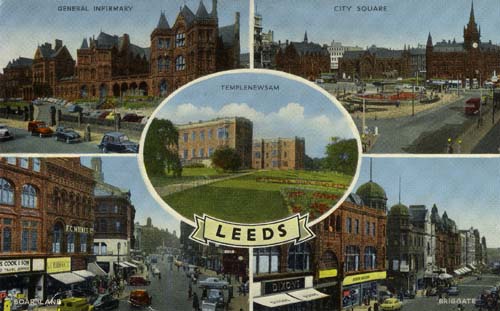

The start, in Wakefield, was an hour later than the two previous days, which was useful. And the rain mostly stopped as we drove there, also useful. It was the most organised we had been all weekend, plenty of time to get a coffee, walk around the buses, see the sign-on and the start before shooting off.

Of course getting away from the town was a living hell. Every road heading out to where we wanted to go was closed, even though the race was taking a different route. For ten minutes we negotiated with a group of marshals, who had cordoned off a 50m piece of road for whatever reason.

Eventually they relented, and we realised that the situation could’ve been solved by just asking straight up for the cones to be moved. Anyway, off we sped, re-joining the route before the first climb of the day at Holmfirth.

There were more marshals there, mostly helpful, some not so much. Raoul got an ice cream, on scoop, vanilla. It wasn’t very good apparently. Some lady shouted “idiots” as we drove off after failing to park on the Côte de Holmfirth. Off to the Côte de Scapegoat Hill then.

At the top there were lots of dogs (see below), and the climb was packed. That’s about all I remember about Scapegoat Hill. It was cloudy too, and a couple of Europcar soigneurs waited at the top. They didn’t manage to hand over any bottles.

Escaping from Scapegoat – Raoul directed traffic, Daniel banged the car door, I tried to charge my phone – this thing isn’t great in a moving vehicle. The radio played this awful song. Everyone hated the radio.

The ride to the Côte de Goose Eye was another fast one, on the single-lane roads and through the small villages that we had become used to seeing. “This is some James Bond shit!” exclaimed Daniel as we crested a hill, airborne again. It’s probably as close to a WRC ride-along as you could find, with Raoul dictating directions like a co-driver, a Timo Rautiainen to Daniel’s Marcus Grönholm.

“Where are Wallace and Gromit from? Here?”

I was unsure myself, but apparently they live in Wigan (in Lancashire), some sixty miles from Wakefield.

Once again we made a mess of getting to the climb. The shortcut to the route saw a marshal open the road in the wrong direction. Thankfully a police outrider arrived soon after, pointing out the mistake. Spectators watched on as we executed another three-point turn on a tiny village street.

A couple of unclassified climbs later (“If this isn’t a côte then maybe it’s a vest”) and we arrived at Goose Eye.

It was steep at the bottom and the village was full of people. A million people came out to see the race apparently, so that’s cool. The top of the climb was less steep and there were far fewer people. We parked midway up the 2.2km climb – another awkward reversing manoeuvre into a crowd of people unwilling to budge. I walked up, Daniel headed back down.

The sun came out, and it was properly warm for the first time all weekend. This random hill in the middle of nowhere also let my phone pick up 3G for the first time, which was nice.

Turns out Nicolas Edet and Lawson Craddock were the Cofidis and Giant-Alpecin men leading the remnants of the breakaway, while the Sky-led peloton was in pieces behind.

I faced a kilometre run downhill to the car but thankfully our way out was to follow the race rather than push through the crowds in the other direction. Running down the grass verge, just about avoiding the cars passing in the other direction, I spotted our grey Corsa and jumped in. Destination, Leeds.

As the race continued north and then east to Leeds, we headed to Bradford ring road and the interminable red traffic lights on the way to the finish. Again, with no real idea of when the riders would actually get to the finish (somewhere between 16:30 and 17:00 according to the roadbook), it looked a real possibility that we’d miss out.

Luckily for us, suburban Bradford seemed to melt into suburban Leeds. We seemed to have made it without really knowing how close we were at any point. Despite our worry, we got onto the course with five kilometres to go, with the convoy nowhere in sight.

After parking there was another marshal confrontation as we were shouted at to get off the road to the car park as if we had no idea the race was coming.

A rush to the finish in Roundhay Park and BMC’s Ben Hermans was the solo winner. There was disappointment for those who had hoped for more GC action on the toughest stage of the race, with the main favourites rolling in together.

After the finish, riders milled about, providing more photo opportunities. And then that was it. The end of the first Tour de Yorkshire. It was pretty fun.

“We’re winning the race. Nobody’s catching this breakaway.” We had missed the press diversion and were now on our second lap of the closing circuit. Daniel was anxious and we had yet to realise that the riders were to complete three laps, not two.

It wasn’t the first mistake of the day. We missed the start altogether after the closed roads somehow caught us by surprise. Well, we didn’t miss it – we got to the press car park, but didn’t come close to where the action was.

Before that I got a jacket. I forgot to take a photo. Here it is. It’s startlingly adequate.

So yeah, we left Selby early, getting on the route way ahead of the race. Stop for coffee, stop for fish and chips, go to the Côte de North Newbald… Hey, where did the race signs stop? Where are all the fans? I guess we drove past the climb? Yep.

We got there in the end but needed to park. People everywhere, obviously, and nowhere to stop. So we should head back down the climb to that spot Raoul suggested then? Yeah let’s try that.

As with any race, the convoy – support vehicles, police and so on – is long. The police outriders come through some twenty minutes before the riders, to close side roads and keep regular traffic at bay. They arrived just as we started to head back down – cue reverse gear, high speed, back to where we just were. A parking spot will have to be improvised.

People are oblivious to the car. It’s a ton of metal on wheels manoeuvring onto a grass verge inches away from them and still they refuse to budge. This was a recurring theme.

Raoul stays in the car as the race passes, Daniel runs further up the hill, shooting the riders, the fans, god knows. I lie in the grass, taking totally pro low-angle shots with my phone. As ever, once the voiture balai (broom wagon) has passed there’s the mad rush to the car, beat the crowds away from the hill, beat the race to the Côte de Fimber, the only other climb of the day.

More thin ribbons of road, hills, troughs, pheasants to dodge, cars to pass. The car was definitely airborne at one point. We get back on the route at Wetwang, arriving at the hill with plenty of time to walk up. The climbs are more straightforward than yesterday’s – lesser gradients, wider roads, not massively interesting.

With a six minute advantage, the break had doubled their lead since North Newbald. Of course we had no idea who was in it, our three phones combined couldn’t muster a wi-fi connection between them, and we had no race radio.

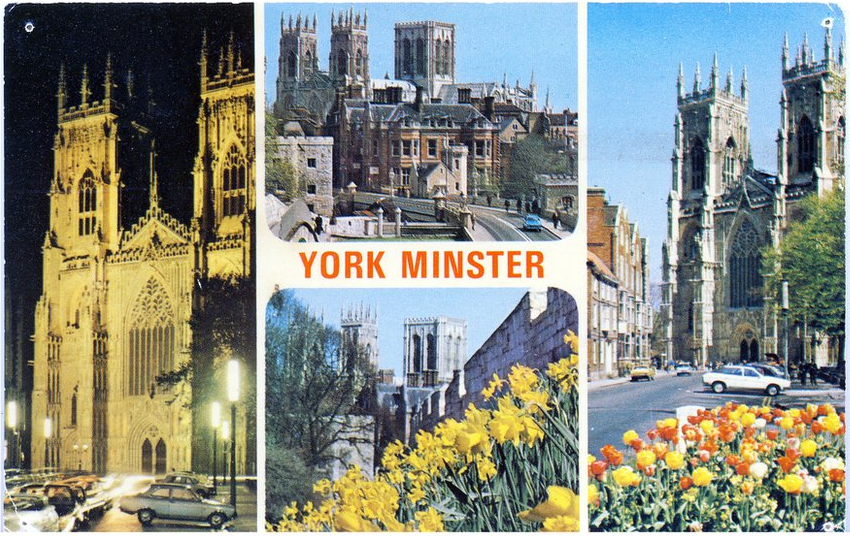

The drive to the finish was less pressing, a straight road to York, meaning we’d be waiting for the race at the finish with enough time to see them pass three times. We should have realised that the press diversion would be at the press centre in York Racecourse (a kilometre out), but we drove past, not realising our mistake until after we had the finish line.

So we did another lap, another tour of York. There was much discussion in the car, arguments even, as we sped through the biggest crowds of the race. Daniel jumped out with two kilometres to go. We’d meet again at the finish, if he could fight through the masses.

He made it, just. He saw the riders twice, but I missed them pass on the penultimate lap – a coffee run in the press room. At the finish there were no interview either – the team hotels were close, so there were no buses to hang around.

Instead we watched the podium, a chance to drink in the ceremony, or rather just leave early because it’s not that interesting. David Millar hung out of the commentary box for a chat about his dinner with Daniel and his upcoming clothing line. Then we hitched a ride to the press room in the broom wagon.

Later we took some time to do some non-race stuff – eating Italian food (spaghetti vongole for me), looking at York cathedral, general mirth, before an evening photoshoot with MTN-Qhubeka back at the hotel. Oh, and I showed Daniel my Milwaukee Bucks t-shirt. He knows they’re real now.

I went to the first edition of the Tour de Yorkshire with Manual For Speed. Stuff happened.

“What really went on there? We only have this excerpt”

Hey, I lost my jacket. It’s April in the north of England and I lost my jacket. It’s April in the north of England and I lost my jacket and I’m at a bike race. Bike races are outside. This is going to be… not good.

Friday morning was ok though. Of course I ate a Full English Breakfast at 8am. That’s the only option at the bed and breakfast. That and coffee, the first of many.

It’s the first edition of the race, the ASO’s Tour de France legacy. I’m hanging out with Manual For Speed. One of them anyway, this guy who wears a shemagh scarf and a Baltimore Orioles cap – “repping my home city.”

His name is Daniel too, and we ‘met’ via email. IRL we meet on Thursday at the seemingly still-under-construction York Racecourse – the press centre. It’s cold, and Bernard Hinault walks past. I stare at him. Later on, I forget to buy a jacket.

Back to Friday, post-breakfast, and an hour’s drive to the coast with this near-complete stranger. We pass Stamford Bridge, a place called Wetwang, while some American woman tells us about roundabouts and left-turns via app.

I got five hours sleep after watching the Milwaukee Bucks crash out the NBA Playoffs with a 54-point loss to the Chicago Bulls. “Milwaukee have a team?” Daniel asks, laughing.

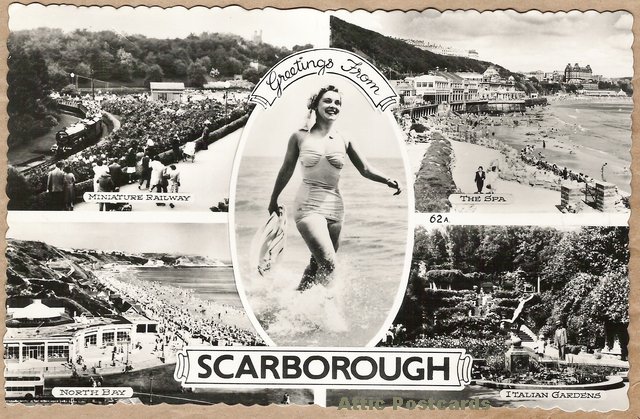

Bridlington is easy, we roll up around half an hour before the start and park the rented Vauxhall Corsa in the place where the press park. It’s eleven in the morning, and cold. There are kids everywhere, a lifeboat on the street, seagulls. Yeah, it’s the coast.

A delusion I know, but there’s always some excitement to wave our passes around and walk where the public can’t. The riders rolling through to sign on, public getting in the way, Merhawi Kudus arriving from Amsterdam twenty minutes before the race is due to start. Standard stuff.

Visa Problems held up the MTN-Qhubeka man, while a delayed flight made things worse. Bad luck for him but better for MFS’s Raoul. He spotted a guy in Castelli-branded uniform at Schipol airport – a soigneur or mechanic or something? No, it was our man Kudus. Cue a long-lasting friendship, despite the minor complication of having no shared language. Cue also, a lift to the race for Raoul.

Once I learned that interviewing Kudus would be something of a challenge, I set off for Europcar’s bus and Namibian champion Dan Craven.

So… are these guys mechanics? Soigneurs? Where is Europcar’s press officer? Who is Europcar’s press officer? It doesn’t matter – I have a plan. I’ll just combine the words ‘press’, ‘Dan Craven’ and ‘interview’ until something happens.

The beard descends from the bus to save me (Can that be his nickname? Maybe it already is.) A quick chat while his embrocation is applied, and the interview is set up – tomorrow evening at the Mercor/Mercury/Mircure (hmm) Hotel.

Back to the car, it’s time to get ahead of the race. The peloton departs, and riders presumably squabble over the breakaway, but we don’t see any of it. Thanks to the incompatibility of the British countryside and wireless internet, it’ll be another hour before we have any idea about what’s actually happening in the race we’re covering.

Did I mention the crowds? They’re big, perhaps unsurprising given the turnout at the Tour de France last summer. Still, everybody waves. Everybody waves at the police too. It’s kinda weird.

The first coffee stop comes after nine kilometres, at the Richard Burton Art Gallery (not that Richard Burton.) We’re going too fast to really think about drinking it though, trading places with the police outriders as the opening climb of the Côte de Dalby Forest looms.

After a few false alarms, a handful of steep hills that don’t show up on the profile, we’re there. Daniel does his thing, photos of the people, a guy stood in a tree and so forth. I talk to Raoul about Diesel jeans and the bomb at the Rund um den Finanzplatz Eschborn-Frankfurt.

Then come the riders. The breakaway. NFTO’s Eddie Dunbar is there – on the attack again in the first race after my interview with him. Two minutes later, maybe five minutes later (who knows when you forget to pay attention?) and the peloton arrives. Marcel Kittel, out with a virus for three months, is already dropping back.

Dodging the team cars and fluorescent-clad fans, there was another uphill sprint to the car. The Côte de Grosmont – four-hundred metres at seventeen percent – is next on the menu, but not before a trip across the North York Moors. We knew they were there, but we didn’t expect them to look like this, so we stopped to take photos. And pee on them.

A Daniel Pasley clutch-punishing parking manoeuvreTM puts us in place for the hill, where we soon find another coffee source – a mobile joint near the top. Thankfully, the speed of our arrival allowed us ample time to stand on the hill. In the cold.

NFTO boss John Wood tells us more about the breakaway. Only there was no breakaway group left on the climb – there was a crash apparently? And they were caught at some point. Dunbar went to hospital in any case. Breton Perrig Quemeneur leads the way up the hill.

Another lung-busting sprint to the car and now it’s the tough part. Can we beat the peloton to Scarborough? Beating car-sickness is a cause closer to my heart – the food, the coffee, the map reading and the roller-coaster driving look to be conspiring against me.

As for reaching the finish first? That was close too – there was much discussion about taking this ambitious route beforehand. Thankfully, the lack of countryside speed cameras only help our cause.

In any case, we made it – but the riders were still some twenty kilometres out as we parked. I was fine too.

Before the finish, the press room beckons – it’d probably help to actually find out what happened today. Oh look, there’s a new breakaway group. Oh look, there are fifty bottles of free beer on the table. I guess I’ll have to come back later.

There’s more running before that though, this time to the finish on the seafront. Nordhaug wins! Kudus is thirteenth! Dunbar is… Where’s Dunbar? Oh.

Finishes are always half-fun, half-stress, but if you have no specific plan of action (today I don’t) then they’re fine. Time to chat to a few people before grabbing a few beers and then heading back to York, soundtracked by some terrible radio (the highlight being a phone-in competition that sees everybody fail to recognise Foo Fighters lyrics). I hope Gap is still open.

It’s the second installment of Future Stars this week, and another Belgian, this time it’s Lotto-Soudal’s neo-pro Tiesj Benoot. The 21 year-old has put in a series of impressive performances already this spring, and starts the Ronde van Vlaanderen for the first time this Sunday.

Benoot has been on Lotto-sponsored teams for the majority of his career, with Immo Dejaegher-Lotto his junior team. He was a consistent performer at that level – 2010 saw him regularly take top ten places around Belgium at races in Lierde, Ichtegem, Steenhuize and at Kattekoers. At the Danish stage race the Tour de Himmelfart he fought for the podium almost every day, finishing up 7th overall.

2011 saw him compete in more international competitions, racing in France and Switzerland and scoring numerous top ten placings. A second place in the Oost Vlaanderen provincial TT championship was a highlight. The next season saw him move to the Avia-Fuji team.

He had a good start to 2012, finishing 12th in the Kuurne-Brussel-Kuurne juniors, but April’s Le Trophée Centre Morbihan saw him in the top six every day and third overall at the end of the stage race. More solid racing at the Czech race Course de la Paix and the GP Général Patton in Luxembourg followed before he went to the Oberösterreich-Rundfahrt in July.

There, after finishing second in a team 1-2 on the first day, he beat Matiej Mohoric to the win on a tough mountainous stage. He eventually took second overall behind the Slovene. More consistent results followed, including third at the Junior Belgian TT Championships and a stage win at Keizer des Juniores.

These strong season-wide performances saw Tiesj selected to the national squad for the Worlds in Valkenburg. On a tough course, he ended up in a creditable 12th place as Mohoric won and teammate Kevin Deltombe took 6th.

Benoot was brought into the Lotto-Belisol setup in 2013, joining their U23 team at the age of 18. He made an immediate impact with a great performance at the Circuit des Ardennes. It’s a 2.2 ranked race, with development teams race against senior Continental teams.

The youngest rider on the team, he was the top performer, finishing in the top five on every day of the hilly four-stage race. He ended up finishing 4th overall and taking the youth and points classifications as he mixed it up with pros Riccardo Zoidl, Markus Eibegger and Andre Steensen.

An 8th place finish at the U23 Liège-Bastogne-Liège and a stage win at the Vuelta a Madrid U23 followed, before he took overall victory at the Tour de Moselle in September. Current Etixx-QuickStep rider Julian Alaphilippe was the man he beat into second place, while two teammates filled out the rest of the top four. Tiesj rounded out the year with a 12th place in Paris-Tours espoirs.

Consistency was once again the name of the game in 2014, his last season at U23 level. Benoot started off with the points jersey and second overall at Le Triptyque des Monts et Châteaux, with a great third place in the sprint at the Ronde van Vlaanderen beloften coming a week later. Later in April came a 5th place at U23 Liège-Bastogne-Liège – chain trouble prevented him from finishing higher up.

The important stage race of the Ronde de l’Isard came in May. Set in the Pyrenees, the four day race included summit finishes at the ski station of Goulier-Neige and Bagnères-de-Luchon. The final day’s racing went over the Col de Port, Col d’Agnes and the Col de la Cort.

Supporting team leader Louis Vervaeke, the big heroics of the race came on the road to Bagnères-de-Luchon as Benoot took to the front in the final kilometres of the stage, driving onwards with Vervaeke and dropping race leader Alexander Foliforov by over five minutes as every group in the race fell apart under the pressure.

Vervaeke went on to win the race, despite Foliforov’s desperate long-range attack. Meanwhile Tiesj finished 4th overall and took the youth classification too – a great performance all round.

Other highlights of the summer included 15th at the Teunissen-dominated Paris-Roubaix espoirs, 5th at Flèche Ardennaise, and 6th at the U23 European Championships in Switzerland. August saw Benoot join the pro Lotto-Belisol team for a spell as a stagiaire, with impressive results such as third place on a tough stage at Post Danmark Rundt and 4th at the hilly GP Stad Zottegem.

After dropping out of the Tour de l’Avenir due to illness, his 4th place at the U23 Worlds in Ponferrada was a late season highlight. As Sven Erik Bystrøm soloed to the win, Caleb Ewan and Kristoffer Skjerping just edged the Belgian out of the medals. Among his last acts before turning professional were an 8th-placed finish at Memorial Franck Vandenbroucke and helping Jens Debusschere to third at Paris-Tours as he finished 16th himself.

This spring, his first few months as a professional, have seen the man from Gent burst onto the scene. Finshing in 8th place at the second stage of January’s Challenge Mallorca was an early season highlight, but the cobbled races of March are where he’s really moved into the limelight.

At the tough Omloop Het Nieuwsblad, his first northern classic as a pro, he was in the front group until the final climbs and finished among the peloton in a creditable 36th place. A few days later he was in the lead group at Le Samyn.

A toughened-up course saw the addition of more cobbles in the finishing circuit saw Etixx-QuickStep with four riders in the eight-man lead group heading into the final kilometres. The powerhouse Belgian squad duly led-out for Gianni Meersman but Benoot helped teammate Kris Boeckmans secure victory, going on to finish 4th himself.

Since then we’ve seen him sprint to third in the Handzame Classic and finish 6th in the horrific conditions at the Ronde van Zeeland. Last week at Dwars door Vlaanderen he put in a huge amount of work for team leader Jens Debusschere. The chasers didn’t catch the Topsport-led lead group but Benoot won the sprint for 6th, an impressive feat considering how much energy he had expended after leading the charge for almost 40km.

He was active again at E3 Harelbeke, attacking midway through the race as the peloton split up and later leading the chase effort up Tiegemberg – bringing down the gap where three BMC riders had failed. He ended up 18th at the finish, and has since been resting ahead of his first participation at the Ronde van Vlaanderen on Sunday.

While he’s had a great start to his pro career, everyone has to remember that Tiesj is still only 21 years-old. With added hills and kilometres, De Ronde will be a totally different animal to the races he has competed in thus far. He’ll be working for Jens Debusschere and Jurgen Roelandts, but it looks like he will be a leader one day.

Benoot balances his racing with studying economics at Gent University. He looks to have a bright future in racing though, describing himself as an all-rounder with similar qualities to Greg Van Avermaet (albeit on a lower level). Going by what we’ve seen so far it doesn’t look like it will take him too long to reach that level.

You can follow Tiesj on Twitter or Strava and keep up with his results at ProCyclingStats.

Finally, if you’re wondering how to pronounce his name, it’s Tee-sch Ben-uut

The cobbled classics are back underway and with the likes of Fabian Cancellara and Tom Boonen coming towards the end of their careers, the focus naturally turns towards youth.

This season we are spoiled for choice with young cobbled talents making their breakthrough. AG2R have Alexis Gougeard, while at LottoNL-Jumbo there’s Tom Van Asbroeck and Mike Teunissen. Meanwhile Etixx-QuickStep can look to Yves Lampaert in the coming years.

We saw two others at Wednesday’s Dwars door Vlaanderen. In the front group there was 23 year-old Edward Theuns, sprinting to second place behind his Topsport Vlaanderen teammate Jelle Wallays to cap a memorable day for the Belgian squad. Just under a minute and a half later came 21 year-old Tiesj Benoot of Lotto-Soudal, winning the sprint for sixth place after leading the chase on behalf of his teammate Jens Debusschere for the best part of 40km.

The two men from Gent will be riding the Ronde van Vlaanderen next week, with Benoot riding today’s E3 Harelbeke and Theuns joint-leader at Sunday’s Gent-Wevelgem. Here’s a look at what Theuns has done in the past, and what is possible for the future. A piece about Benoot will follow later.

Theuns started out at local club Koninklijke Gent Velosport, combining cycling with playing football for KFC Merelbeke. After some strong results he moved to junior team KSV Deerlijk-Gaverzicht for 2009.

The most notable alumni of the team is the legendary Briek Schotte, winner of two World Championships, two Paris-Roubaix and two editions of the Ronde van Vlaanderen. Others that have passed through the ranks include Marcel Kint, Johan Bruyneel, Patrick Lefevere, Nico Eeckhout and current Etixx-QuickStep rider Julien Vermote.

Back to Theuns and he won his first race (the junior version of the Beverbeek Classic), taking seven other wins before changing team in 2010. The destination was VL Technics Abutriek, which would be his home for the next four seasons.

Combining racing with university studies, Theuns was successful straight away, winning a bunch sprint in the Triptyque des Monts et Châteaux stage race. Among the men he beat were now-familiar names like John Degenkolb, Taylor Phinney and Jetse Bol, all of whom were riding for much bigger development squads.

His second season was tougher, the only win coming in a smaller race at the end of the season. 2012 saw him participate in the Ronde van Vlaanderen espoirs for the first time as well as becoming the time trial champion of East Flanders. Later in the year he finished in the top ten of Paris-Tours espoirs.

The final year before turning professional was his best yet with consistent performances throughout the year. Spring saw him win the time trial at Triptyque des Monts et Châteaux before finishing sixth at Liège – Bastogne – Liège espoirs and then taking the mountains jersey at the prestigious stage race the Giro della Regione Friuli-Venezia Giulia.

A podium spot in the Belgian U23 TT Championships followed, before finshing eighth at the road race. His reputation as a strong time trialist was further enhanced by a win in the prologue of the Ronde van de Provincie Ost-Vlaanderen. Theuns rounded out his time as an amateur with a call-up to Belgium’s Worlds team and another eighth place Paris-Tours espoirs.

ProContinental team Topsport Vlaanderen came calling, and last year Theuns turned professional. He had a solid start at his new team, taking 21st at Omloop Het Nieuwsblad, sprinting to third in the Handzame Classic and finishing Paris-Roubaix.

August was the best month of his first year as a professional though – he outsprinted Marcel Kittel to take third on stage two at the Arctic Race of Norway. Days later his first professional win came at the GP Stad Zottegem, as his team played the finale to perfection for Theuns to win a two-man sprint against Wanty’s Tim De Troyer.

2015 has seen him step up a gear, and three months into the season Theuns leads the UCI Europe Tour by 89 points. He started the season in France, taking seventh at the hilly GP la Marseilaise before consistent riding at the Etoile de Bessèges saw him take the points jersey fter four top ten finishes. Fifth in the sprint at the Clásica de Almería followed, and then a tough time in the mountains at the Vuelta a Andalucía (along with two top ten finishes) set him up for the start of the Belgian season.

Finishing 14th at both Omloop Het Nieuwsblad and Kuurne-Brussel-Kuurne were decent results, especially given how tough the former was. It wouldn’t be much longer until better results came though, winning the sprint from a five man lead group at the Ronde van Drenthe after riding on the front for most of the final kilometre.

The next day he was fourth at the Dwars door Drenthe, before taking fifth place at the weather-affected Ronde van Zeeland Seaports – a race which saw just twenty riders finish. We all know what came next, but we don’t yet know what is to come. Sunday sees the chance to measure himself against some of the best sprinters in the world as Kristoff, Sagan, Cavendish, Degenkolb and Greipel fight it out at Gent-Wevelgem. Beyond that, the big challenges of the Ronde van Vlaanderen and Paris-Roubaix..

Theuns has come to wider prominence on the cobbles, and that looks to be where his future targets lie. Theuns is a great all-rounder though – he is a strong sprinter, can time trial well and can get over hills too. In terms of style, Greg Van Avermaet seems a good comparison to make.

As is usually the case with talented Topsport Vlaanderen riders, a move to the WorldTour beckons. We have seen Kris Boeckmans, Sep Vanmarcke, Yves Lampaert and Tom Van Asbroeck all make the move in recent year, and with Theuns’ contract up at the end of the year it looks like he will follow.

You can follow Edward on Twitter here, and view his palmares here.

Finally, the time has come and the report we have all been waiting for has been released. At 228 pages in length it’s a bit of a slog, and with a great deal of emphasis on the past.

There’s talk of all the familiar faces – the tales of Hein, Lance and Pat are covered at length. We hear about the 1990s and the ‘period of containment’ that focused on limiting the health risks of doping rather than a policy focused on catching every wrongdoer.

Many pages are dedicated to failures in governance that occurred a decade or more ago, and there’s even a section walking us through the history of doping. We all knew how bad the past was – and now we have an official document to prove it. Almost as soon as it was released we saw a number of all-encompassing summaries of the report, including articles by the always great inrng, and Peloton magazine.

Rather than focus on the past though, I want to look at what it the report has to say about the current state of cycling, and what it could mean for the future. Here’s a look.

A turning point in anti-doping

With the cesspool of the 1990s behind us, and the Armstrong years already covered ad nauseum lets fast forward to 2006. The period from that year to 2008 is highlighted by CIRC as a turning point in the fight against doping. “Steady improvements and a growing willingness to combat doping at its roots” are cited.

It was indeed a period of change. At the UCI’s anti-doping unit with Lon Schattenberg (a man who shared the same ‘avoid scandals’ mindset as Verbruggen and McQuaid, notably writing letters to teams informing them of drug detection windows) left to be replaced by the Australian Anne Gripper. Other changes in personnel included the dismissal of a large number of doping control officers, described as receiving little training, prone to leaking information and often being close with teams.

With Gripper came a raft of changes. Targeted testing was brought in, while more and more out-of-competition tests were carried out. The Cycling Anti-Doping Foundation (CADF) was also introduced during her time at the UCI and funding for anti-doping was increased. An often unnoticed part of the fight – the introduction of post-race chaperones is also noted.

“UCI started to systematically use chaperones in 2008. However, it took some time for the chaperones to serve their purpose. Part of the reason for this, was due to sport-specific logistical obstacles (difficulty of spotting riders, packed finish area). By 2010 it was acknowledged that the chaperone-system was, in principle, working well.”

The biological passport

The biological passport (ABP) was brought in under Gripper’s watch in 2008 and has been hailed as a big advance in anti-doping. We have seen in the past that it isn’t a foolproof tool though, and the report tells us that there are deficiencies for riders to take advantage of – much like the 50% rule, it limits how much riders can dope, rather than eliminating doping altogether.

“In interviews with riders and athlete support personnel it appeared that the basic problem was that athletes would go to the limit of what is detectable and this has not changed. Furthermore, the incentive to try out substances that might give a performance enhancing effect, but are not on the prohibited list is still very present in the peloton.”

Meanwhile there are other problems. The report has found that riders are able to fine-tune doping programmes using ADAMS software – an unintended consequence but a disturbing finding. It is noted that riders can use the software to “assess and monitor their blood values and make sure that they stay within pre-defined parameters through fine-tuning.”

Further criticisms of the passport include the lengthy procedures involved in sanctioning riders (the Menchov and Kreuziger cases are cited), and the “conservative approach” of some of the ABP experts in wanting to pursue ‘doping scenarios’ thanks to the difficulty of analysing nuances in data. While we have seen dopers hide behind excuses like training at altitude or dehydration before, but they can be legitimate reasons for odd blood values. It’s a fact that only makes the job harder for the experts.

So how clean is cycling today?

There were varying responses in the report, and it seems that riders know about as much as we do. According to the CIRC, a common response when asked about how teams was “probably 3 or 4 were clean, 3 or 4 were doping, and the rest were a “don’t know”.”

One rider was asked about cleanliness levels in the peloton and put the figure at 90% but said he thought that “there was little orchestrated team doping” anymore. Another rider felt that 20% were doping, while many stated they just didn’t know who was clean and who was not. Of course, we don’t know who these riders are, so we have little idea of which figure is closer to the mark. And that’s before we get to the question of what riders view as ‘doping’.

Meanwhile new methods of doping such as ozone therapy and AICAR are brought up, while CIRC also includes a staggeringly long list of substances that riders are currently using, or have been during the past few years. There’s even a small section dedicated to the possibility of mechanical doping, something that has been raised several times in the past.

These answers aren’t surprising, but they aren’t heartening either. None of us can safely say which number is more accurate, but we do know that the days of massive gains from doping are gone. The report echoes this, saying that “10-15% gains have become a thing of the past.” Instead, performances are enhanced perhaps 3-5% by new techniques such as microdosing.

So the playing field still isn’t a level one, but going by these figures it’s more level than it used to be.

Loopholes

Despite the heartening numbers, more work still needs to be done, as CIRC notes a number of ways in which riders are still gaining an advantage. The problems with the ABP have been outlined above, but there are further loopholes for riders to take advantage of.

The no-testing window between 11pm and 6am is one. CIRC states that, “riders are confident that they can take a micro-dose of EPO in the evening because it will not show up by the time the doping control officers could arrive to test at 6am.” This is a difficult problem to solve though, with the human rights of riders factoring into the equation.

Often a controversial topic, TUEs are another problem, with interviewees reporting that they are “systematically exploited by some teams and even used as part of performance enhancement programmes.” The abuse of corticoids and insulin in particular raise concern, while there was also a feeling that obtaining a TUE is too easy. One anonymous doctor told CIRC that corticoids were often used for weight loss as opposed to their stated function of pain relief.

Finally, concerns are raised regarding the use and abuse of substances not on WADA’s banned list. One rider talked of a ‘pill system’ he used, which involved him taking up to 30 pills a day, while also reporting the use of tranquilisers and anti-depressants on his team.

The report lists a various array of nutritional and homeopathic substances along with painkillers, caffeine tablets, Viagra and Cialis, with CIRC having been told that all were taken with the sole purpose of substance enhancement in mind. Just think back to the Kovalev brothers to get a glimpse of what this looks like.

Tramadol use has also been in the news in the recent past. It cropped up again here, with interviewees of the opinion that if a rider needed to take it then they shouldn’t be racing. Similar sentiments were recorded regarding corticoids.

Conclusion

So no revelations then, but a lot of information about what is going on in the peloton today. Or at least what is presumed to be going on – the lack of evidence and a reliance on hearsay is a problem. Proof is hard to come by though, and in this case we have to make the best of what we’ve been given.

There are some disappointments – look at the list of names and you only see 16 riders with Chris Froome the only non-retiree. Ten others have declined to be named, but Francesco Reda and Mauro Santambrogio are dead certs. 26 is still a very low number though, and the question of credibility comes up.

In any case, it’s less important to dwell on the individual stories than it is to think about what can be done in response to the report. While everything we have read might not be totally reliable, the raft of ideas that have been proposed seem, on the face of it, to be very useful.

At this stage they are somewhat vague but each idea is something the UCI needs to take notice of. There’s talk of intelligence sharing with governments as well as more intelligence gathering within CADF. On the testing side we read about re-testing samples and testing riders at night. Also mooted are sound ideas like a whistleblower desk, a review of the TUE process and improvements to the ABP.

If the UCI has changed – and both the commissioning of this report and the contents within point towards that being the case – then we can cross our fingers and hope that changes like these will be implemented. There’s still a long way to go, but things can get better.